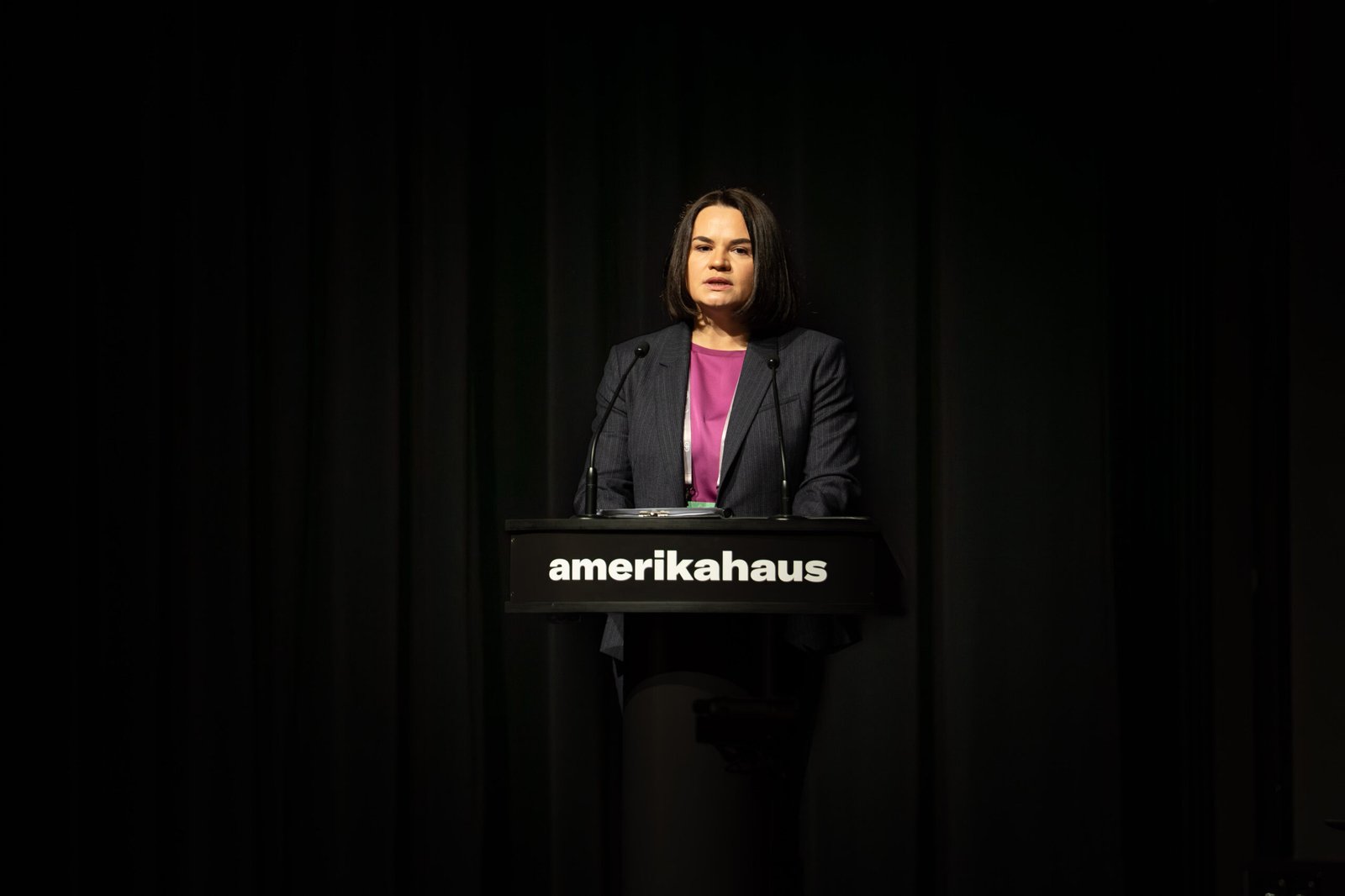

On February 14, as part of the Munich Security Conference, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya took part in a youth side event titled “The New Public Square is a Screen: Rethinking Democracy in the Digital Sphere”. Around 200 participants joined the event, including students, young experts, representatives of civil society, researchers, and journalists.

The event was organized by the Munich Security Conference in cooperation with AmerikaHaus, the Office of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, and Junge DGAP, the youth network of the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP).

Alongside Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the discussion featured:

- Janine di Giovanni, Executive Director and CEO of The Reckoning Project;

- Edith Kimani, DW News Africa correspondent in East Africa;

- Kari Odermann, political scientist and communication specialist;

- Katja Muñoz, Senior Research Fellow at DGAP’s Center for Geopolitics, Geoeconomics, and Technology;

- Natalia Valeria Müller, Munich Regional Coordinator at Junge DGAP.

The panel was moderated by Natalia Valeria Müller and Alina Kharysava.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya devoted her remarks to the role of digital space as a new public square, where political agency, solidarity, and resistance are increasingly being shaped today.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya:

«Dear Excelencies, dear friends,

Good morning.

They say if you want to understand global security, you should come to the Munich Security Conference.

And if you want to understand what real resilience means — try doing it with almost no sleep.

That’s the spirit of Munich: many crises, little sleep, and very honest conversations.

Yesterday, from the stage we heard a lot about a “new world order.” Many said the old one has already been destroyed, and the new one has not yet been built.

Yes, there is a real risk that a world based on values could weaken or even disappear.

But on the other hand, in this “brave new world,” we also have a chance. A chance to rebuild and strengthen what was broken. Our freedoms, and our security.

The case of Belarus shows how democracy and security are intertwined — and one cannot exist without the other. A dictatorship that does not respect its own citizens – becomes also a threat to its neighbors.

The case of Belarus also shows the power of technology and media. They can serve good and strengthen freedom — it can connect people, expose truth, and support civic action.

But in the hands of dictators, the same tools become instruments of manipulation, surveillance, censorship and repression.

What should empower society can be turned into a weapon against it.

And finally, the Belarus case shows how fragile democracy is: it is so easy to lose, and so hard to get back.

In Belarus, everything started 30 years ago, when one day newspapers were published with blank frontpages – the report on Lukashenka’s corruption was censored. Dictatorship started with establishing control over the media.

The dictator has built a parallel reality for society — playing on fears, nostalgia, and empty promises.

Maybe some of you have seen the German film “Good Bye, Lenin!” It shows very well how propaganda works: it creates the “right” picture of the world, builds comforting illusions, and keeps people passive.

When people believe everything is stable and under control, they stop asking questions. They stop participating.

You know, myself, I stayed away from politics all my life. I was just a housewife, a mother of two. Like many others, I was told that politics is dangerous, that it’s better not to get involved, that there are “smarter people” who know better. And many of us lived in such an illusion.

With no doubts, technology has changed everything. Sometimes people ask me: what made your movement possible?

“God bless the Internet” – I say.

The Internet became a safe space for millions of Belarusians. A place where people could speak freely, find each other, and organize.

Students, professionals, IT specialists, doctors, workers — people who had never been involved in politics before — suddenly had tools to connect.

ICQ and Skype, Bluetooth and 3G, Facebook and YouTube, Signal and Telegram, VPNs and ChatGPT – these weren’t just technologies. They were catalysts for change. They became our tools in the fight against dictatorship — tools the regime couldn’t fully control.

In 2020, for the first time, thanks to technology, we managed to prove our victory in the presidential election. A platform called Holas (“The Vote”) helped us organize parallel vote counting. Then millions of people took to the streets.

The protests were coordinated through the Telegram messaging app, and the KGB desperately tried to find the “organizers.” But there were none — it was completely self-organized.

Even when the regime shut down the internet during the protests, people used different tools to exchange information and coordinate.

When the regime blocked major media outlets, people created so-called “courtyard chats,” bringing neighbors together and helping them organize locally.

These chats first appeared during the COVID pandemic, when people tried to support one another while the authorities ignored the crisis.

Of course, the regime quickly took measures: massive repressions followed, almost all media were declared extremist, many banned, thousands of people got arrested, many had to flee.

But even from exile, independent media managed to restore their work, while most of their audience remained in Belarus and accessed content through cloud services and VPNs.

TikTok became another major discovery — and a powerful media tool — for millions. Unlike some other platforms, you can consume content without leaving obvious traces for the KGB. TikTok — largely agnostic to political views — has given people access to independent content and real news.

Technology didn’t only strengthen the media, but the resistance itself. One of the most important groups are the Belarusian Cyberpartisans.

Many times, they hacked government websites and databases, leaked important information about the war, about repressions, or revealed names of KGB agents. Based on this information, the journalists are able to investigate the regime’s crimes and abuses.

Yes, it’s truly irritating to the regime, but inspiring for the people.

After 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine from Belarusian territory, another project was launched by civil society – Belarusian Hayun, which is basically a chatbot, letting people to share information about the movement of Russian troops, and helping Ukraine to defend.

I have been in exile for five years, but I cannot say that we have lost connection with people on the ground. Through tools like Zoom, I have weekly calls with people inside the country, and we still have an impact and influence on the situation in Belarus.

Our IT specialists have developed a secure digital ecosystem to empower Belarusian citizens within and outside the country. You can simply install the application SVAE and become part of this ecosystem.

There, people can speak freely online, organize themselves, take part in large-scale programs, such as crowdfunding or participatory budgeting, and even vote.

In 2023, we held online elections to the Coordination Council, which is one of our three main democratic institutions. We are preparing for the next digital elections in May – it will be really hot.

Sometimes, we experiment with AI too. Two years ago, when Lukashenka has held another fake elections, we’ve created a democratic AI candidate, called Jas Haspadar.

Trained on real people’s hopes, Jas offered vision and dialogue. Amid mistrust and suspicion, reigning in dictatorship, people chatted freely with Jas, as if he was a real person. But his biggest advantage was that he couldn’t be jailed.

Of course, using digital tools comes with many risks.

Dictatorships also learn to use technology – to surveil, to manipulate, to spread their narratives. In good hands, technology can serve for good. But in the hands of dictators – they can make the lives of people a nightmare.

That’s why it’s so important to build partnerships with tech companies, and keep them on the side of good, on the side of democracies.

That’s why it’s so crucial that tech cooperates and supports independent media, with civil society, the democratic actors.

That’s why it’s so crucial to strengthen digital literacy, especially in non-democratic societies, like Belarus – so people can use these tools in full.

Technology is not neutral — it chooses sides through use and design. We must ensure that it strengthens democracy, not sustains dictatorship. Tech giants must stop regimes from abusing global digital platforms.

And, last not least, technology can help strengthen national identity – which is so important right now in Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova. For example, still, many platforms don’t support Belarusian language, which often leads people to go and consume Russian content.

In our case, national identity, language, and culture – is also a weapon against the so-called “Russian world”.

Dear friends,

The battle for democracy is taking place literally everywhere, from Kyiv to Tbilisi, from Cuba to Iran. This battle also rages in codebases and clouds. And I know that we can and we will win this battle – together.

Thank you very much,

Zhyve Belarus!»